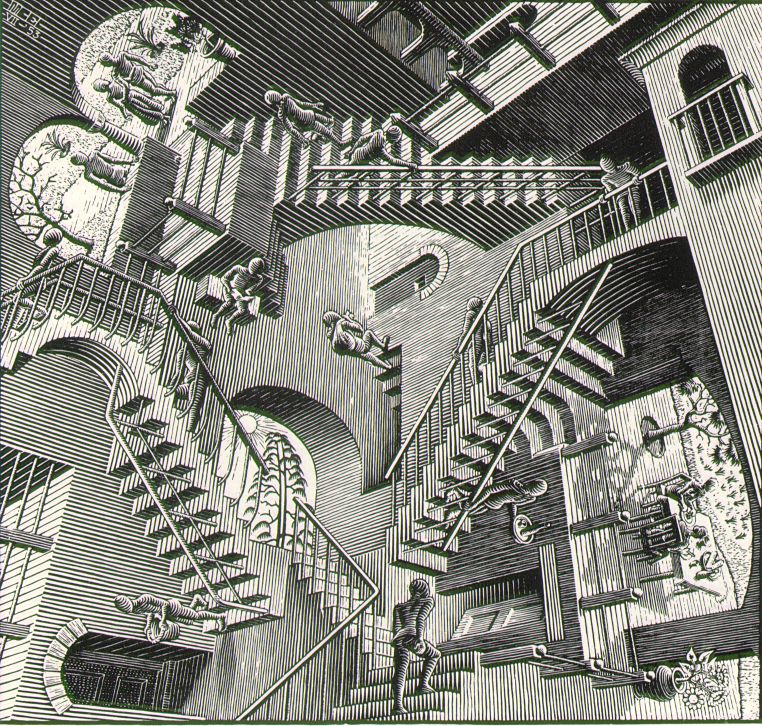

If M.C. Escher had written a whydunnit he might have called it Ripley.

I say this because the recent Netflix masterpiece starring Andrew Scott and written & directed by Steve Zallion (he of Schindler’s List fame – more on that later) is an Escherian nightmare of wrong turns, about turns, smart turns and climbs that lead to nowhere.

The plot (Patricia Highsmith’s genius cannot be overstated here) is one of the most elaborate and thrilling I have ever encountered. The world’s greatest crime writers thrown in a room together could not have conjured up anything more magical even if Jesse Armstrong had been put in charge of them. It’s not that it’s full of cliffhangers, as such, it’s the sheer chicanery that Tom Ripley demonstrates as he shape-shifts his way through the lives (and deaths) of himself and his unwitting benefactor Dickie (Deekee) Greenleaf that make this story so compelling.

But let’s start after Highsmith and look at what Steve Zallion brings to the party. Well, for a start, the script is terrific. I don’t know the novel so I don’t know if it’s laugh out loud funny – but this sure is. One might grumble at his mild mocking of Inspector Pietro Ravini’s occasional flaws with the English language, especially his pronunciation of Freddie Miles’ (Meeles) name, but Vittorio Viviani bring a wonderful blend of Inspector Clouseau and Poirot to the part that is delicious. His mild OCD is amusing and that is one of the themes that run through the movie.

Zallion can never have had as much fun making a film as here. He plays tricks with the audience from start to finish and his elaborate use of repetition (posting the mail, riffling through notebooks, application of pen to paper, placing of items on bureaux, zooming in on concierges, framing of the post office, police cars, the cat, stairwells, paintings, drinking (or not) wine, ashtray purchasing, mimicking of Caravaggio and Ripley) is bonkers and dazzling.

The central motif of climbing stairs is extremely interesting. I have two theories on this. 1) it represents class climbing – Ripley is a wannabe, a charlatan and a grifter. He aspires to greater riches and stature and is deeply uncomfortable in society situations such as at Peggy Guggenheim’s party in Venice where he is in real danger of being found out for not being one of ‘us’. He’s always climbing to attain his goal. 2) it represents the futility of the whole police hunt, the whole story, as Ripley outwits every character (even the reasonably savvy Marge) by shifting the sands, rearranging the staircases so that we reach that ‘going nowhere’ outcome that Escher so brilliantly portrays in his paintings.

And lastly there’s his choice of monochrome to create a film noire, but also a work of art. Art is a central metaphor of the series. Caravaggio’s work, his homosexuality and his murderous past are all reflections on Ripley’s own story. Ripley loves Caravaggio with a passion because he admires not just his work but his lifestyle. The fact that Greenleaf’s wannabe painterly skills are appallingly lacking is just a bonus.

The cinematography has to be seen to be believed. Mostly spot on (it’s occasionally a touch overexposed) by Robert Elswit (He’s PT Anderson’s go to guy and won an Oscar for There Will Be Blood – bosh!). It drives the mood and the beauty, aided by a strong soundtrack, and has its moment in the sun when he stunningly, and frankly hilariously, references Schindler’s List with a single step of blood red cat paw prints. One second of red in eight hours of monochrome. You know the scene I’m talking about in both productions, right? Episode 5 if you missed it.

And then theres the acting. Johnny Flynn I could take or leave, Dakota Fanning played her irritating role to perfection (entitled little Sylvia Plathesque romanticist that she is). I’ve talked about the marvellous Vittorio Viviani, but the stars of the piece are the deliciously camp and truly dislikable Eliot Sumer who gets his just desserts as Freddie Meeles and, of course, the joy of Andrew Scott.

What can I say about Andrew Scott that hasn’t already been said? In the last five years he has risen from nowhere to challenge Steven Graham as Britains top actor. I think he has more range than Graham but both are a delight every time they hit our screens.

In this Scott OWNS the screen. His arch, sometimes befuddled playing of the unintended villain that is Tom Ripley is extraordinary. He falls into his murders rather than premeditates them so that makes him OK, right? And we are desperate for him not to be caught, because Scott has intoxicated us with his charm, his humour and his intelligence, all hidden behind a relatively blank canvas of a face. In moments of stress you can see the brain ticking, by micro-movements of Scott’s demeanour. This is acting of the highest calibre and Ripley, not the victims, is our hero.

We love Andrew Scott, therefore we love Tom Ripley.

You might have guessed by now that I loved this. A straight 10/10.